Takeaway #1 – The name is about decision-making

Takeaway #2 – We use parameters hundreds of times a day

Takeaway #3 – Great parameters, which are built on clear ideas of what you want, lead to great decisions, plans, policies, and practices.

When I tell someone about my new consulting business, this is the first question they always ask:

“What’s the name?”

And it always surprises me. I expect people to ask what I do or how I help. But there must something about a business name that feels more important. A business name gives people a better way to react. Either they like the name or they don’t. Also, the name is something that separates me, a friend, from the work. The name is a thing that delivers an easy-to-digest first impression. It will either sound familiar or alien, cool or boring, smart or dull.

Or, in my case, it might sound curious. Because when you name your business “Parameter,” it naturally leads to the next question:

“What does that mean?”

In some form or fashion, I explain by saying this:

“‘Parameter’ represents the things that limit yet also liberate us. The better we understand this idea, the better we do the things we do. Which, you know, is what my business is all about.”

This never seems to satisfy. So for anyone who remains interested in the name, here is the rest of the detail:

Search the dictionary for “parameter” and you’ll find definitions that relate to statistics, engineering, and computer programming. It feels crunchy. Data-driven. Highly technical.

Yet, there is nothing more natural. We think in parameters all the time. The Collins Dictionary <link> has the best explanation for this. It defines the word as

“a limit that affects the way something can be done or made.”

The limit could be budget parameters. Or time parameters. Or a quality standard. The parameter is the standard. It is the baseline expectation that leads us to make all manner of decisions. Want to choose a restaurant for tonight’s dinner? You will undoubtedly use some parameters to find the best option. Those parameters are built on the situation you face and goal you seek.

So let’s imagine it is a regular weeknight and you just got off from a long day at work. You’re hungry. This hunger leads to a decision problem: what do you want to eat? Something at home or something from a restaurant?

You decide a basic direction—to eat out. No cooking, no leftovers. You’re too tired for that. But where do you go? There are restaurants all around you.

Given the situation (hungry and tired), you decide you want something that is within a certain budget—in terms of both time and money—and also familiar and comforting. But not too comforting (i.e., indulgent). After all, it’s a weeknight. And since it’s a weeknight, you want it to be quick. But you don’t want fast food, either. Sound familiar? This mix of countervailing preferences is what make our first parameter. It’s not very useful but it gives us a clear sense of what we DON’T want.

That narrows your options from ~50 to something more like ~25. Not exactly a workable number. So you start thinking more about what you DO want. Tonight, you want food that is wholesome, with minimal processing. You also want to take it home. No need for dining in tonight. This is your next parameter.

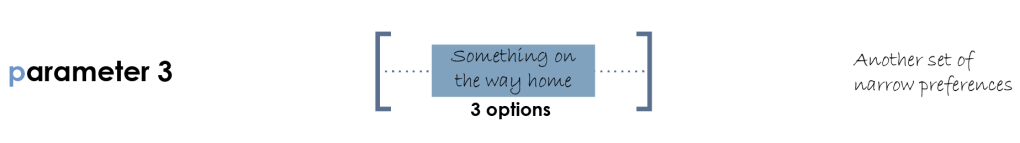

Notice the options tightening? ~50 possibilities is now down to ~10. There’s more precision, more preferences, and a clearer sense that your money will be well-spent with whatever fits this general set of alternatives. Yet, it still isn’t enough, is it? After all, if you’re getting takeout, you can’t get it from some faraway place. You want something that is conveniently located along your normal route home. This is your next parameter.

Now we’re getting there. Three are only options that fit this compounding set of criteria: the local restaurant called Marco Polo’s, the franchise sandwich shop, and the Greek place with your favorite salad.

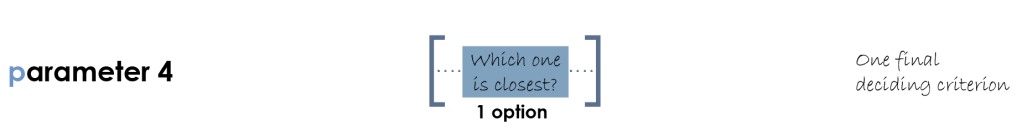

Again, any of these work just fine according to your parameters. But you can’t go to all three. You have to settle on a single option and so you use one final, deciding criterion: convenience. You’re tired, traffic is rough, and so you decide you’ll go to whichever option is closest to your current location.

Which means you’re getting the Red Curry with Chicken tonight from Marco Polo’s. After all, it’s right across the street! You could walk to it! Thus, a decision is made.

This is how we do things. We regularly go from broad sets of options to a single choice built on a set of filters I just-so-happen to call “parameters.”

If it sounds complicated, rest assured that it isn’t. The process I just described for choosing dinner is much quicker than it seems. Maybe two minutes? Or five? In any event, we often run this calculus and process these parameters with quick, confident ease.

Of course, we’re not perfect. Some parameters get ignored. Some are barely even understood. And thus, some decisions are irrational. To err is human and no one, especially a consultant, should tell you otherwise. We make mistakes. Through them, we get better. This is why my firm carries this name. It starts with the broad idea and narrows itself down to something more precise and effective with each client’s project.

Consider all the things that happen in local government. There are goals to be met. Conditions to be improved. Rules to be enforced. Each of these things are a set of parameters. Many of these parameters are defined by the policies, plans, and practices we create. Some of it is common knowledge. Some of it is intuition. All of it is for the sake of making things better.

This is a fine goal. But how we get there is where the real art and science behind our work. The more clearly we understand how we operate, the more likely we will do the things we hope to do.