A Brief Summary of the Five Elements:

- A clear, singular, evocative goal

- An approach rooted in physical planning and design

- Less, but better, through the regulation of leverage points

- Graphical depictions for every design standard

- Clear, objective, numerical standards.

Here’s a sentence my teenage self would have never imagined me writing today: I read lots of zoning ordinances. Lots and lots of zoning ordinances. And it’s kind of fun. Fun in the way that archeology must be fun. In both cases, you discover relics of the past that connect you to a bygone era when people—just like you—lived with the same issues and needs as today.

I know that’s a stretch for some but remember that every zoning code is a product of the past the instant it is published. Each code was written and reviewed by well-intentioned, hard-working professionals who, like us, did their best to balance the special interests, concerns du jour, and timeless practices of responsible stewardship. Sure, each code is flawed. Even the newest ones will be somewhat out-dated. But so it goes. Our work will soon be seen in the same way.

It’s craftsmanship nonetheless—humbly produced like the fragments of pottery we find at an archeological dig.

Some people don’t want to believe this. Some find it easier to imagine old and new zoning codes are written by a cabal of industrialists who create special rules for sprawl and automobile dependency. Or worse, some think these codes were drafted in dark, smoke-filled rooms where political insiders willfully design policy to prohibit multifamily housing in 70% of a city’s geographic footprint.

That has happened. Really. But not as often as we think. The more common truth is that all the pitfalls of zoning codes are the result of unintended consequences. These broad, multi-faceted policy documents—arguably the most complex policy documents in local government—attempt to regulate how everything is built and operated. After all, zoning is designed to protect health, safety, and general welfare. That’s basically … everything.

Such an enormous scope isn’t an inherent problem but the devil is in the details. Ask anyone who tries to revise one of these codes once it’s reached the size of a 300+ pages. Every rule has a reference to another rule, so that revisions to one requires revisions to another. Whole sections of language get repeated often, and used as some form of bedrock justification for a particular practice. Until there’s a legal challenge and the City Attorney decides the wording is too vague. But when the wording is replaced, the result introduces terms and concepts that are less effective, more limited, and then you need several more new sections to accomplish what one simple, powerful paragraph had done for decades. Bloat is the result.

Then there are the obscure scar tissue policies, the narrow stuff that happened once and compelled new policy to make sure it won’t happen again—regardless of the likelihood. You’ll often see this in the development review process. Something oddly specific will emerge like “application fees shall be paid solely in United States currency” because, one time, someone tried to pay their fee by bartering vegetables instead of giving money.

That actually happened once.

It is simply inevitable that policy documents of this nature will have errors, require revisions, and suffer flaws. Indeed, when it comes to writing zoning ordinance, I think the greatest of all mistakes is to enshrine the idea that you can avoid mistakes. Painful as it is to admit, mistakes are inevitable. Every new policy, amendment, revision, and addition will have cracks.

We know how to fix those. We’ve been doing it for decades. This article isn’t about that. Instead, years of practice have led me to think less about the errors we want to avoid and more about the successes we want to achieve. Zoning cannot be made perfect. But it can be designed to be really good at a few things. What are those things—those vital few things that redeem the rest of the flaws? Below are the five elements that I think answer this question.

1. A clear, singular, evocative goal that ties it all together

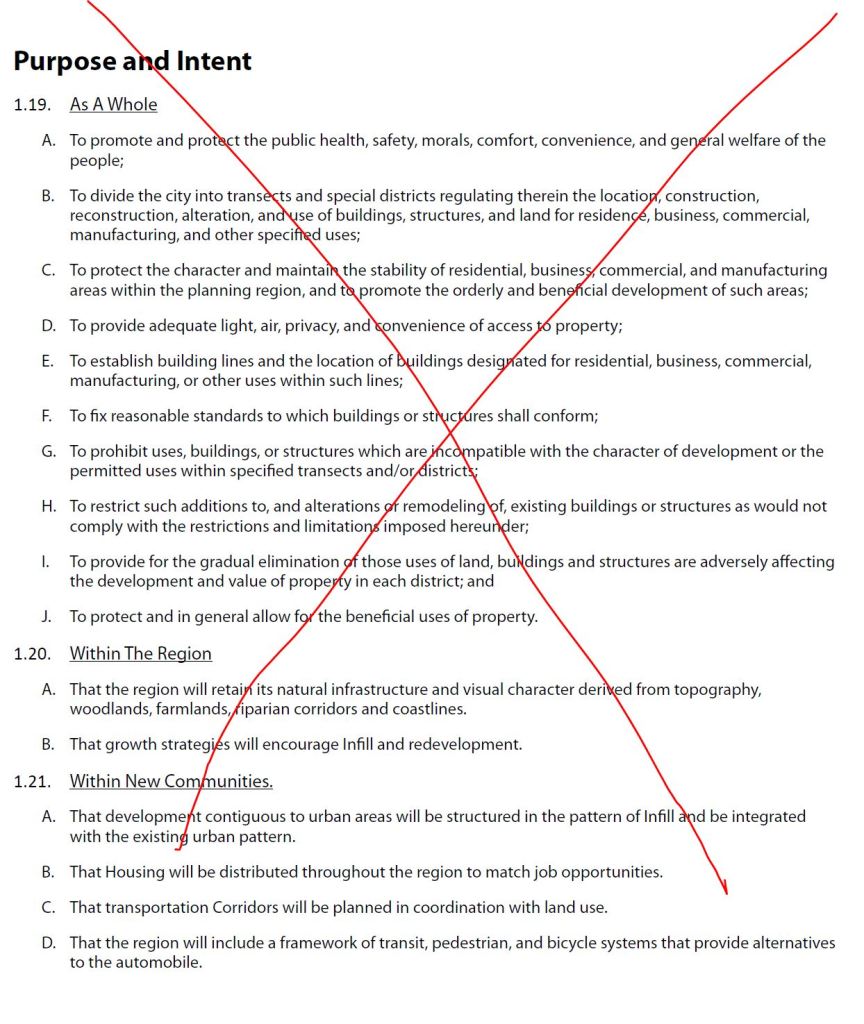

Most zoning ordinances come with a long preamble that reads like it was written by the founding fathers. We usually called it the “Statement of Intent.” Few read it. And because it is usually very lengthy, very broad, and very redundant, few of the subsequent policies have a clear, direct connection to this important section of the code.

For example, here is an old “Purpose and Intent” page from a code I wrote long ago.

It’s too much! Or rather, it’s too concentrated.

Too concentrated? Yes. I can explain.

A great code should start with a strong, powerful, all-encompassing goal. This usually relates to “public health, safety, and welfare.” But those terms are not very helpful so I’ve developed a model goal statement to demonstrate something better. This single line might not be enough to satisfy the attorneys but, for the sake of writing effective policy, I think it helps a great deal to state something like this:

This zoning ordinance is established in order to …

“foster an accessible, resilient urban form that accommodates and adapts to human needs over time.”

Anyone reading that might feel like it isn’t enough. So again, an attorney can add some garnishments. The key is that the goal is clear enough to establish a good rationale for all the regulation that follows. Why do you require setbacks and restrict land use and do all these other things? Because it achieves the goal of this ordinance.

This, however, is the tip of the iceberg. You should then infuse additional goal/intent language in a more narrow context for every additional section of code. Why do you regulate FAR? Why restrict these land uses in Zone A but not in Zone B? These questions need answers and the best way to express them is with “guiding principles” for administration and straightforward objectives that define desired outcomes.

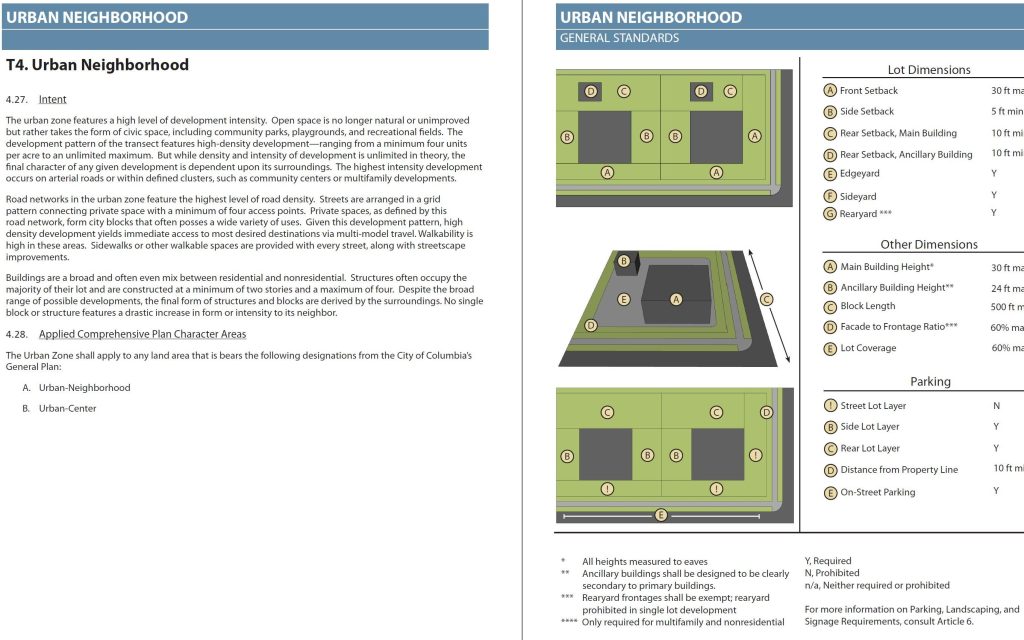

The next section will demonstrate a simple example of this idea. Take a look at the graphic for the zone called “medium density detached.” You’ll see it has a description of the outcome the rules are designed to achieve. It also has some guiding principles for how to regulate the area more broadly. This is just one example of how to approach the idea.

2. An approach rooted in physical planning and design

Like building and fire codes, the zoning code should be written as a means of ensuring that the built environment—the physical changes occurring to the land—is optimized for safety, health, and welfare. That means that design standards should be prevalent throughout the code. In fact, design standards should comprise the bulk of the code’s power.

We somehow lost sight of this when we dove deeply into fine-grained use restrictions. The subsequent rise in form-based codes has been a welcome correction to that old trend. It was once blasphemous to say this but I can now confidently state, without controversy, that 70-90% of all land uses are perfectly fine in any urban setting so long as the setting itself is properly designed. The physical form and function is what a great code will address—without busying itself on the differences between accounting offices and dry cleaners.

3. Less, but better, through the regulation of leverage points

I’ve written multiple papers on this topic so anything here just belabors the point. To learn more about leverage points in zoning codes, check out this paper on zoning minimalism written for the APA: . And soon, I’ll have a massive follow-up (70+ pages!) written for the Mercatus Institute. I’ll post a link when it’s published.

Suffice to say that there are elements of the built environment that are deeply influential to good physical planning, design, and function. If we don’t get those vital few elements right, all will be for naught. To think about this, consider the following question: what is the most important rule in your zoning ordinance? Opinions vary but one of my personal favorite answers comes from the former Planning Director for Nashville, TN—Rick Bernhardt. Rick is an innovative champion of great codes and, when asked this question, his immediate answer was “build-to lines.”

The APA article demonstrates why he’s right. It is one of ten basic, simple rules that I think make a great place. These rules, address critical aspects of the environment, are like leverage points. Move these in the right direction and everything else will follow.

4. Graphical depictions for every design standard

Decades ago, urban planning programs lost their emphasis on graphic design. I don’t know how it happened but I, for one, didn’t learn anything about art or illustration during my Master’s program. Yet, the ability to communicate our ideas visually is the most impactful skill we can develop—so much so that I took it upon myself to learn everything I could once I started my first job. My career opportunities improved dramatically from that point forward. Not because I’m great at illustration (I’m decent) but because people desperately need illustrations to understand what we’re talking about.

It helps us all. And it hopefully shows how a zoning code is as much about education as it is regulation. We are governing things that laypeople do not understand. Density, form, function, and scale are not intuitive concepts. At least, not without illustration. Great zoning codes communicate these things visually, so people can grasp the whole point of it all, and this simply cannot be done with words alone.

5. Clear, objective, numerical standards.

How many shrubs? What size for your signage? How far away does a nightclub have to be from an elementary school? How tall is too tall for buildings in this area?

Great ordinances have simple answers to these questions. The answers are expressed as numbers, measurable and discrete, and there is no room for discretion or wiggle room for either the builder or the reviewer. The code is more predictable and both parties benefit.

I think everyone appreciates the idea of clear, objective, numerical standards. Yet, I occasionally hear talented planners say that some things cannot be easily regulated with numerical standards. They suggest that things like the “desired character” of an area or the “compatibility” of a certain land uses cannot be reduced to mere quantities.

Yet, when we dig deeper into such topics, we always find that the reason is due to a vague definition of these terms. Vague concepts lead to vague rules. Which gets us back to Number One—the need for clear goals. Without them, everything else gets quite blurry quite fast.

Need an example of all these things in action? Check out Nashville’s Downtown Code. It remains the gold standard in my humble opinion. Simple, clear

There you have it. The five elements of a great, modern zoning code. It’s so easy, right? Of course not. These ideas are simply the guidelines for future work. They serve as the common ground for what is good about every zoning code I’ve seen. Mix it with a particular approach for writing these codes (minimalism; less but better) and you’ll not only make a better policy, but also create better process and—ultimately—better results.

Isn’t that what it’s all about?