Takeaway #1 – Area plans need the full involvement of the entire local government, especially Public Works, Parks, Finance, and Administration

Takeaway #2 – Real success requires capital improvements. Thus, 40 – 60% of the work should be dedicated to solving the funding problems.

Takeaway #3 – Planners and Planning Departments should not be left to do it all alone.

In the first part of this series, I covered the power and importance of small area plans—when done well. These plans tackle important, unique problems yet often limit themselves to zoning revisions and a handful of new policies for the private realm. I don’t think this is enough.

Especially when you consider the long, arduous journey we take to reach those policies. We’re talking hundreds, maybe thousands, of hours. It’s absurd to me that we spend all this time on these areas, creating their tailored visions, only to watch the capital improvement plan (i.e., the thing that can make the vision a reality) get developed and implemented separately, as an island unto itself, with hardly any consideration for the plan that’s been delivered. I don’t blame the Public Works Department. Or the DOT or FHA or MPO. I blame the faulty approach that brings about the small area plan in the first place. I blame our misplaced faith in zoning and codes. I blame the organization that fails to build the right team, and project scope, at the start.

Take a look at the Montgomery County sector plan (link). Visit the Design Vision on page 87. It’s a beautiful description of what might be. The focus is on the physical form and function and you’ll note that the very first paragraph says this will be a “walkable and bikeable village.” It will have a “small street grid” and “pockets of green that protect existing and future canopy trees.”

Sounds amazing, right? I want to see this get build now. Today. I’m sure the author wanted that, too. But it can’t happen in the way we desire. We’re just the planners, after all. We work with people to create these visions and then wait/hope/dream for someone else to build it.

It shouldn’t be this way.

Specifically, the passages that I just highlighted are all the things that should be built by the Public Works department. These things are are elements of the public realm. And my guess is that the Public Works department doesn’t have the resources to do any of those things right now. My guess is that they will have to rely on private investment (i.e., new development) to make these things happen. And if past experience is any indicator, the private investor will fight hard to avoid the responsibility because, well, they don’t have the resources either.

I sympathize with both parties. And this is why 40-60% of the energy expended on a small area plans should be directed towards the reconciliation of these differences. 20 – 40% of the effort should go into the visioning, to figure out what we want to do with our public realm; 40 – 60% of the work should be dedicated to solving the funding problem. And 100% of this should be resolved before the plan is published. Otherwise, is it really a plan?

In some ways, a plan written without a funding strategy is like a charity donation written on a bounced check. The intentions are good but the promises aren’t kept. Again, I should repeat: no planner wants that. No author of any plan—comprehensive, small area, or otherwise—wants to create visions that remain unfulfilled. And yet, without tightly-coordinated public investment, this is the fate we often face. Otherwise, how will we know that the street grid will emerge? How will we know the private realm will be fashioned in the way we desire? The public realm is the foundation upon which the rest of the vision is built.

The Montgomery County plan recognizes this on page 102, the Implementation section of the plan. It is five pages long, roughly 4% of the entire document. It starts with the revisions to the land use map and zoning regulations. Those are big, albeit incomplete, improvements. Next is a list of CIP projects that are slated for action. These are listed without cost estimates, timeframes, or prioritization. These projects are “potential” improvements. There is no clarity or coordination on what, if anything, will be done among this list of items. There is no pressure (in the document, anyway) to make these happen.

The same is true in my old Cherrydale Area plan which I wrote for Greenville County, South Carolina in 2009. And likely for the same reasons but I don’t want to presume. In my case, the lack of detail on public improvements are due to the fact that I did not, could not, engage the Public Works department. They had no money or time to deal with this part of town. So I crafted a vision without them, highlighted the needed public investments (pg 92-97), put it on a timeframe that no one agreed to, and hoped for the best. The plan was adopted but those improvements have not been built. How could they? If it isn’t in the CIP, it isn’t going to be.

I, as a humble planner, couldn’t make that happen. I don’t think my department could, either—even with all our combined strength. We needed Public Works. We needed Administration. We should have had all the hands on the deck, so to speak. Instead, the project was relegated to me and the team and we did what we could. Through zoning. Zoning helped. But again, to belabor the point, nothing will change a place more than proper capital improvements and right-sized facilities.

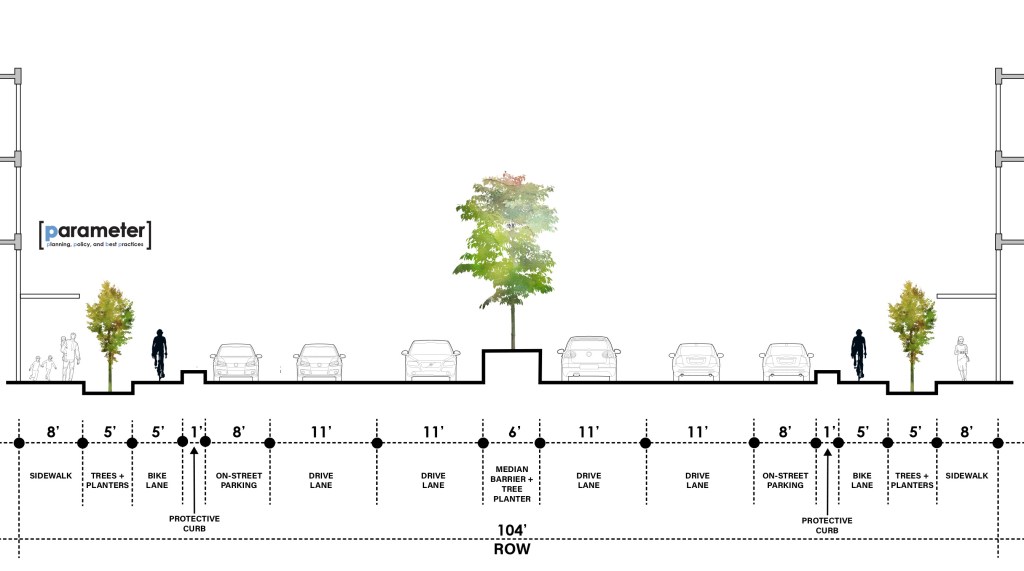

All I wanted was to convert a wide, dangerous 5-lane highway full of local traffic into a safe street with trees, benches at the bus stops, planted medians, bike lanes, and slower traffic. Is that so much to ask!?

Maybe. If so, it’s a sign that the organization isn’t ready to do a small area plan. This isn’t anything to be ashamed of. In fact, the notion of “readiness” and organizational capacity is the most critical determining factor of any successful plan.

In conclusion, small area plans are deeply powerful. Or they can be. Because these plans operate at a scope and scale that can spark actual, on-the-ground change. When scoping these plans, remember the following truth: physical infrastructure does the work of zoning in a fraction of the time and with better results. Use it to your advantage.

Want to limit development in Montgomery County? Don’t extend sewer and don’t add more parking lots.

Want to ensure a rural feel to the surroundings? Establish a public greenway and multi-use path along the perimeter.

Want to create pedestrian-oriented clusters of development? Build a small street grid in 500×500 property blocks with complete streets that only provide two vehicle travel lanes, on-street parking, no traffic lights, and no access along the highways that lead into the new development node. And while you’re at it, sync the development policies in this tightly-confined area to a T4 transect a’la SmartCode.

Want to reinvest in a dying corridor a’la Cherrydale? Invest deeply at the area with the highest potential for urbanization. Add street trees, a pocket park, benches at the bus stops, planted medians, bike lanes, and gateway signage. Then, in Phase Two, replace the lighting with pedestrian scale features. Underground the utilities through a local improvement district. And sync the development policies in the entire district to a T4 transect a’la SmartCode.

These solutions might not be perfect but you get the idea. Area plans are an opportunity for us to return to the grand practice of physical planning. Area plans operate at a scale that helps us develop visions for the public realm. Yet we spend so much of our time in the private realm with zoning because we, the planners, appear to be the only ones creating the plan. Using the only tool we exclusively control.

This isn’t enough. We know it and yet we try our best. So consider this a friendly reminder, from a colleague and (hopeful!) consultant, that we can do better.

Small area plans are an incredible opportunity for a local government (not just the planners) to make an impact on the public realm. It is an opportunity for us to work with residents, engineers, architects, landscape architects, and many more people to create real visions of the future. It is a chance to realize those visions with coordinated investment and intelligent policy.

Village centers? Vertical mixed use in the inner ring? Shopping mall redevelopments and new city blocks with complete streets? Greenways, parks, and community centers? All those things are possible in a small area plan.

This is the underrated power of small area plans. This is the most exciting work we can do.

So don’t use your pencil to merely draw the lines of a zoning district boundary. Draw the road diet. The next sidewalk extension. The next park and connected trail system. Bring your buddies from Parks and Public Works into the mix.

It’s easier said than done. I don’t fault myself or the authors of the Montgomery County plan for any lost potential. We did our best with what we had. The organization probably wasn’t capable of anything more. So to make sure we can tap the full potential of a small, area plan, read the next article in this series about readiness. Is your local government ready for this kind of work? There are four key indicators to answer that question and its coming soon in the next article.